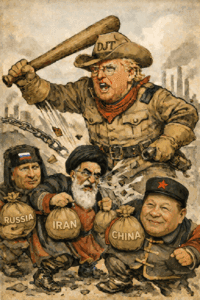

IN VENEZUELA, TRUMP TARGETS CHINA, RUSSIA AND IRAN

By Marco Vicenzino

3 January 2026

The capture of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro and his transfer to New York to face U.S. indictment are being read largely as a dramatic episode in U.S.–Latin American relations. That view misses the larger point. The episode functions as a strategic signal—one that speaks less to Caracas than to the broader recalibration of U.S. deterrence in an increasingly contested new world order, with implications for rival powers well beyond the Western Hemisphere.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s target audience extends well beyond Caracas. His message is calibrated for China, Russia and Iran, and arguably select others —states that have long treated Latin America as a low-risk arena for influence projection.

That assumption has been visible in Beijing’s economic penetration through debt, energy and infrastructure; Moscow’s security ties and intelligence cooperation; and Iran’s logistical and security footprint in Venezuela and parts of the wider region. Each has tested U.S. tolerance for years, operating on the belief that the hemisphere was strategically secondary for Washington.

Maduro’s capture is intended to puncture that belief. The signal is that proxy influence, grey-zone activity and strategic freelancing in the Americas will now carry tangible costs.

Trump’s move against Maduro involves multiple motivations, including economic and legal considerations. Above all, however, it is geopolitical. It reflects the realities of a new National Security Strategy and an emerging Trump doctrine—one that redraws U.S. red lines and reasserts deterrence as a governing principle.

What Trump is signaling is not a Venezuela policy in isolation, but a reassertion of U.S. strategic intent in its near abroad—and beyond where core interests are at stake.

From the administration’s perspective, after years in which hemispheric instability was managed, compartmentalised or quietly tolerated, Washington is making clear that the Western Hemisphere is once again central to U.S. strategy—not a permissive space for drift, criminalised governance or unchecked external power projection.

At the core of this approach is a redefinition of boundaries. Latin American governments are being told that sovereignty will no longer shield regimes that fuse state power with transnational crime, narcotics trafficking and illicit finance. By foregrounding indictments and legal accountability, the United States is reframing geopolitics through enforcement and deterrence rather than diplomacy alone. Leaders who criminalise the state are being treated less as political counterparts than as security threats.

Allies, too, are being addressed. Washington is signalling a renewed willingness to act without full consensus when it judges core interests to be at stake—moving first and managing diplomatic fallout later. This marks a departure from an era in which caution often substituted for clarity.

Critics will argue that such actions risk eroding international law, inflaming regional opinion and setting precedents others may exploit. They will warn that unilateral force, even when legally framed, can undermine the norms the United States itself relies upon, and that escalation in the hemisphere may prove difficult to contain. For them, these concerns go to the heart of global order and U.S. credibility.

Yet to dismiss Trump’s gambit as a replay of past U.S. interventions is to miss the distinction being drawn. This is not Iraq. It is not Afghanistan. It is not an open-ended project of occupation or nation-building. It is Trump’s deliberate effort to restore deterrence in a region long treated as geopolitically settled.

Ultimately, this episode will be judged not by the legality of one operation or the fate of one Venezuelan leader, but by what follows. Deterrence succeeds only if paired with discipline, clarity and restraint. Whether this recalibration stabilises the hemisphere—or invites escalation—will shape regional and global politics for years to come.